Tug capsized during operations

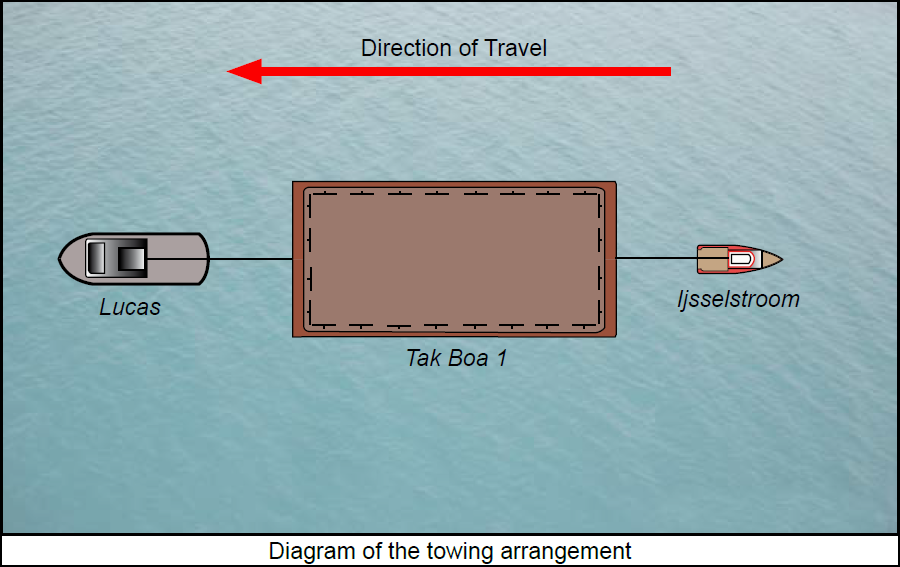

A member reports an incident in which a tug girted and capsized during towing operations. A third-party contractor’s tug was acting as a stern tug for a heavily laden barge arriving in port. The master of the stern tug chose to deploy the towline over the stern of his vessel, and intended to maintain position and heading relative to the barge by using the tug’s engines. A bridle (Gob) wire was not rigged. As the lead tug increased speed, the master of the stern tug found that he was unable to effectively control the yawing of his tug, and five minutes after connecting to the barge, the vessel took a large sheer to starboard, girted and capsized. The crew escaped without injury.

Our member conducted an investigation and noted the following:

- For a conventional tug, towing over the stern, particularly while running astern, is an inherently unstable mode of operation;

- The towing speed was too high in this instance;

- The lack of a bridle wire or ‘gob rope’ meant there was no physical safety device to prevent the tug from girting when directional control was lost;

- The tug’s master had not been trained in the use of the emergency brake release, had not tested it or witnessed its effect, and could not operate it from the bridge when the tug got into difficulties;

- There had been no prior toolbox talk or discussion between the pilot and the tug masters regarding the entry of the barge into the port, and the pilot was unaware of the intended towing method or operational limitations of the stern tug;

- Crew were working an 18 hour ‘changeover’ period in breach of the relevant working time regulations;

- The tug masters’ knowledge and experience were never assessed by the third-party owner, and there was no formal staff training program.

Our member drew the following lessons:

- There should be prior discussion of scope of work between project manager and vessel owners, and between masters and pilots, to ensure suitability of vessels and crews, and full understanding of the task at hand;

- Clear instructions on operational procedures should be provided to all personnel involved in operations;

- Risk assessments and toolbox talks involving all relevant parties should be carried out prior to all towing operations;

- Personnel should be familiar with emergency brake release systems on tugs and test it or witness its effect;

- There should be appropriate implementation and understanding of working time regulations;

- Towing over the stern:

- Speed should be kept at an appropriate minimum, not more than 3 knots, when a tug with conventional propulsion (single or double) is acting as a stern (steering) boat;

- Captains of towed vessels should remain aware of using the propulsion, and the combination of forces acting on the hull;

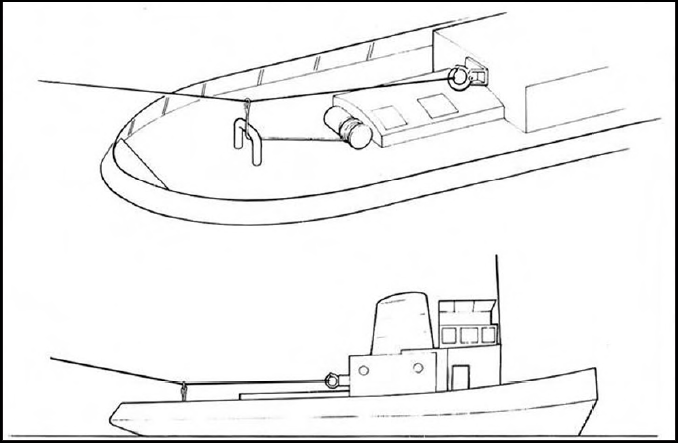

- The use of a shot string (standard on single propulsion, advisable on double propulsion vessels) helps to keep the towing wire on the aft ship centrally positioned and avoids girting, the towing point being brought to the aft of the ship instead of on the pivot point of the tug. See example in Fig. 2.

Safety Event

Published: 27 September 2010

Download: IMCA SF 06/10

IMCA Safety Flashes

Submit a Report

IMCA Safety Flashes summarise key safety matters and incidents, allowing lessons to be more easily learnt for the benefit of all. The effectiveness of the IMCA Safety Flash system depends on Members sharing information and so avoiding repeat incidents. Please consider adding safetyreports@imca-int.com to your internal distribution list for safety alerts or manually submitting information on incidents you consider may be relevant. All information is anonymised or sanitised, as appropriate.

IMCA’s store terms and conditions (https://www.imca-int.com/legal-notices/terms/) apply to all downloads from IMCA’s website, including this document.

IMCA makes every effort to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data contained in the documents it publishes, but IMCA shall not be liable for any guidance and/or recommendation and/or statement herein contained. The information contained in this document does not fulfil or replace any individual’s or Member's legal, regulatory or other duties or obligations in respect of their operations. Individuals and Members remain solely responsible for the safe, lawful and proper conduct of their operations.